I’m so lucky that you are my best friend

Picture my Russian nesting doll. Crack me open around my waist and find a smaller me inside. Some alterations have been made to fit the same design on shrunken dimensions. Here, less strands delineate my hair. There, one fewer button puckers my jacket. Inside this smaller self is another self, more shrunken still, more rudimentary. You keep cracking my smaller selves open at the waist until you reach my smallest self, solid wood. Where I was once an intricately decorated art object with discernible limbs, hands and feet, I am now a suggestion of a person, a swaddled blue blob with a face. Out of every shell, this is the closest thing I have to a true self.

Fossilized inside at her most vulnerable stage, my smallest doll is 16 years old. She eats lunch alone at school. Her mother is the only one who texts her. She participates in no extra-curricular activities, wastes hours each day after school browsing the Internet, tunneling for something she never finds. She stays up too late finishing the homework she pushed off, then wakes up late again the next morning, never rested. Her hair is greasy, her pores are clogged, and her doctor tells her she ought to lose weight. She pops Tums in Spanish class for the heartburn.

She does not have a single friend in the world.

The sour summer came and went, the kid turned 17. September returned in its usual sawdust, but, this time, it brought Tamia through the choir classroom doors. Everybody knew Tamia, everybody loved her. They put her picture all over the school website, trusting her dentist’s daughter’s smile to win them fresh tuition checks. Intelligent and self-assured, she was a light source, a candle crossed with a spotlight. She was funny, she was kind — a real, grinning girl. And, compelled by forces beyond logic or reason, she would become this loser’s closest friend.

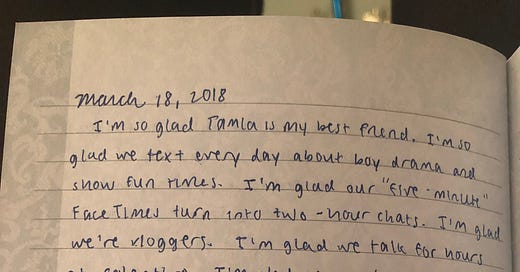

We were both Cancer Suns with Aquarius Moons, like Princess Diana. Maybe it was fated, how we stumbled into lockstep. We played out routines that were novel to me: we FaceTimed on the weekends, got coffee after school, texted bunches and bunches and bunches. We made vlogs for the school plays, gossiped about our crushes, shared Spotify playlists. For Tamia, this was friendship, it was normal, of course. For me, this was the first year of my life.

I’d been squinting up at the same hilltop for so long, barefoot on jagged rocks, incapable of taking a single step. It was as though Tamia had brought me a new pair of walking shoes and set an uphill pace for me to match. When we reached the crest, it was not as hard-won as I’d anticipated when I’d been frozen in the lowlands. I stood a moment at the peak. I could see it all: the low-down life, not mine any longer, the untapped terrain ahead of me, more glorious than its mystery.

But there are only so many breaths to catch before the thousand-mile feet ache for motion again. I began barreling down the other side of the hill at a weightless sprint. Something irreversible had shifted. I didn’t check to see if Tamia was following me. I just assumed she was.

.

Are your lights still on? I’ll keep you safe if you keep me strong.

In our second year at college, Tamia and I began to fight. Over text, almost all of it, thousands of miles apart. I always started it. I assumed that, when Tamia looked at me, she always saw my smallest doll. I’d get sensitive. I’d fail to articulate how her words had hurt me, but I made it clear that they had hurt. She didn’t understand what the problem was — and maybe there had never been a problem to begin with. Maybe we were just closer than was natural. Is it still a tug of war, if both parties keep holding the rope, but stop trying to pull each to the other’s side?

I had begun building a new container for myself. It was a chrysalis, it was an embryo. It was an oversized shell picked up by the pinching hermit crab. I was ashamed to speak to anyone who already knew me, in case they’d pick up on the changes I was trying to make before they were complete. To everybody I was meeting afresh, I was her already, that different person. I’d done the unimaginable: I’d convinced these new friends that I was cool.

This newest nesting doll engulfed all her predecessors. She fit snugly, and she looked remarkable. I wanted to glue her shut around me. I befriended stunning people, creative people, moneyed people. The more proximity I gained to them, the closer I felt to absorbing their traits for my own avatar. I stared out at the pretty lights, woozy on the cliff’s edge. I swore I would never go home again, never relate to people who couldn’t understand California cold.

When the pandemic promptly shuttled me back to the forsaken homestead, these illusions vanished. I played dress-up in the clothes I hadn’t brought along to the dorm room. They hung like dust and they smelled like sawed wood. I got on a Zoom call with the high school friends, because they were the only ones that seemed real under the conditions. Campbell’s soup only gets my attention on sick days.

There had lately been a braindead Instagram trend, in which folks felt compelled to post an unflattering photo of themselves for one day only, then delete forever. Tatyana, a girl from high school who had never really been my friend, posted a photo of the two of us for the trend. It was from our junior homecoming dance. I was 16.

I was galled. My long-buried smallest doll, exposed in the online wilderness. The butt of a near-stranger’s joke, again. I brought it up in the Zoom conversation hoping for support, but laughing, in case I didn’t get it. They must’ve only heard the laughing, because everyone on the call went to screenshot the photo off of Instagram and set it as their Zoom backgrounds. I exited the call, stifling tears, and I left the group chat soon thereafter. Before I went, I sent a bullshit message about how the energy of the group wasn’t really my vibe at this point in time, but I’d still love to stay friends with everyone individually <3.

And that was it. I was alone again. But I’d chosen it, this time. I looked in the mirror, and I saw another lacquer shimmering around my image. The numbers were preset, I only had to paint them in. No more prehistory, only the fantasy. No more graveyard, only the factory. No more landfill, only the hospital.

.

I tell you all the time, “I’m not mad.” You tell me all the time, “I got plans.”

The friends I see most have different names these days.

Alana hung up the phone. She didn’t say it outright, but I’d upset her. It was an accident. The buzzing didn't go away for hours.

I pick at my fingernails when I sit beside Keiva. I suspect she has less to say to me, now that her old best friend stopped disappearing.

Cami is going to be out of town on my birthday, and she feels bad about it. I tell her we’ll make other plans when she’s back in town again. She still feels bad, says I’m one of her closest friends. I think it, but don’t say it back.

I buy Noah a scoop of ice cream. He’s been driving me to rehearsals ever since my car broke down. He tells me he hopes I know I don’t owe him anything. I realize I was worried I did.

Weeks go by since I last checked in on Sophia, and I struggle to find a way to reach out that doesn’t feel contrived. I don’t laugh with anyone else the way I laugh with her.

I’m going to throw myself a birthday party this year. I hope against heaven that enough people that actually like me show up for it.

.

Me and you, we could do better, I’m quite sure

Tamia came to visit Los Angeles for a conference last week. By extension, she visited me. We’re working adults now, so, out of her multi-day trip, I only got to see her the night that she landed. We met up with Tess for Italian in Miracle Mile. It was loud and I was embarrassed to find myself the only one ordering a glass of wine. We talked TV shows, new jobs, love lives. We headed back to my car, aiming for drinks at the Formosa, but there it was instead: the El Rey Theatre, aglow in neon, Jensen McRae on the marquee. Tamia was a fan, Tess and I were unfamiliar.

“I could maybe get us in,” I offered.

I wasn’t sure it would work. I’d quit my job there a few months before, surrendering my free concert privileges along with the employment. But, when we walked up, Caro lifted the velvet rope and Julian waved us through the security check. I grinned my hellos to Maya and Andreas, sheepish out of uniform, relieved to find their eyebrows raising in recognition. Tamia, Tess, and I angled into a spot near the front, off to the side and uncrowded.

The concert was sweet. I didn’t know any songs except for the covers. Jensen McRae was tall and graceful, anachronistic in a sparkly silver unitard and large framed glasses. I stood behind the other two, so as not to block either’s view or knock them off balance with a brush from my oversized tote bag. I watched them watch the concert. Tess, who was only my friend because of Tamia. Tamia, who used to watch every concert by my side. Tamia, whose contact photo in my phone is still her at Lollapalooza 2019, turning around to pose against a lilac twilight, a light-up balloon shining behind her like a puffed-up false moon. When we talk on the phone, Apple autofills her professional headshot instead. I like my picture better, but I’m not sure whether either picture has any business representing her. I’m not sure whether I have any business writing about her, but I couldn’t write about anything else.

I dropped her off at the hotel twenty minutes before my car broke down. She understood when I had to cancel our Sunday breakfast plans. She went back to Milwaukee without seeing me again, but we’ve been texting like we live down the street. We shared our locations with each other, indefinitely. If I were to start driving to her now, it would take me 31 hours.

I have a feeling she’d wait for me to get there anyway.

.

😭😳😏

I love you loads, this was beautiful 🥲🤍✨