i saw the imaginal disk glow

A spiritual tour through two of my favorite releases of 2024: Jane Schoenbrun’s I Saw the TV Glow and Magdalena Bay’s Imaginal Disk

(Spoilers ahead, if you mind that sort of thing)

As stubbornly as I’ve avoided admitting it, I can no longer deny: networking has value. When my coworkers discovered me waiting in line for the final US show of Magdalena Bay’s Imaginal Mystery tour, I was not only permitted, but encouraged to cut to the front. I waltzed right into the venue while the GA plebeians were kept waiting on the street. For the first time in my life, I wound up with a prime spot in a sold-out crowd — third row, dead center.

The kids beside me struck up a conversation as we waited for the performance to begin. It was all fun and friendly until they revealed that they were high school seniors. They’d assumed I was also 17, which I first found flattering, then more damning than when I’d been presumed to be 28 a few weeks prior. Feeling pride when a stranger lowballs your age is an acute sign of getting old.

The kids claimed me still, though I could tell they felt a little betrayed by my adulthood. They reassured me of my youth, firmly pulled me over to the Gen Z side of the ongoing us vs. them tussle with millennials. They reminded me of all the friends of friends I spoke to in acquaintance clumps at high school dances and football games. They were so nice, so starry-eyed, so ephemeral. These connections always end the same: an unspoken I’ll see you when I see you, if ever again. The social contract only exists in the tête-à-tête, and it binds me to grins and giggles and nods along with your opinions, even if I don’t really know what you mean. Anything to get you to like me, please.

I wonder whether I’ve grown much at all since 17. I think I’ve made choices that would make a younger me proud, bypassed the hometown glory track in favor of leading an interesting life, even though it’s a little unstable. If 17-year-old me could look into the future and find my present-day self waiting for her, I think she’d breathe a sigh of relief. Then, she’d ask me: So, does it go away?

And I’d tell her the truth. It doesn’t. Every single day, I moonwalk through my life under the light pressure of the feeling that there is another, better life for me out there, and it is close enough to feel, but not to touch. It’s the reason I’m thousands of miles away, sobbing on the phone to my mother like I haven’t done in years because I’m terrified I can’t hack it in the big city. You would think I’d been blindfolded, kidnapped, and dragged here unconscious in the dead of night, the way I complain about the place.

But I chose this. It went against everything I had come to recognize as my life, everything that brought me comfort and purpose. That feeling, that light pressure, built up over time and eventually forced my hand down on the detonator. Boom, up in flames. And, miserable as I’ve been, I know like broccoli that it was the healthy thing for me to do.

In I Saw the TV Glow, Owen doesn’t leave. At the end of the movie, he’s still there, in the suburbs, in the Midnight Realm. Towards the middle of the film, though, he gets desperate enough to try. We find him with his head shoved straight through the TV set, sparks and noise and smoke pooling around him. His rat-eyed father pulls him out, douses him in the shower. Owen — who has always been so reserved, so unsure — is inconsolable. He’s screaming: THIS IS NOT MY HOME.

A couple weeks after I saw TV Glow, I spent the length of a thunderstorm convinced that I was living inside the movie. I was on the couch in my basement apartment —but, really, I was Isabelle in the grave, heart ripped out of my chest, drooling out Luna Juice while shovelfuls of dirt fell rhythmically down on my prone body. The real me was somewhere dark, somewhere far, and I was too dead, too numb, too scared to find her. In my chest, Owen’s voice echoed like the scream had been my own: this is not my home.

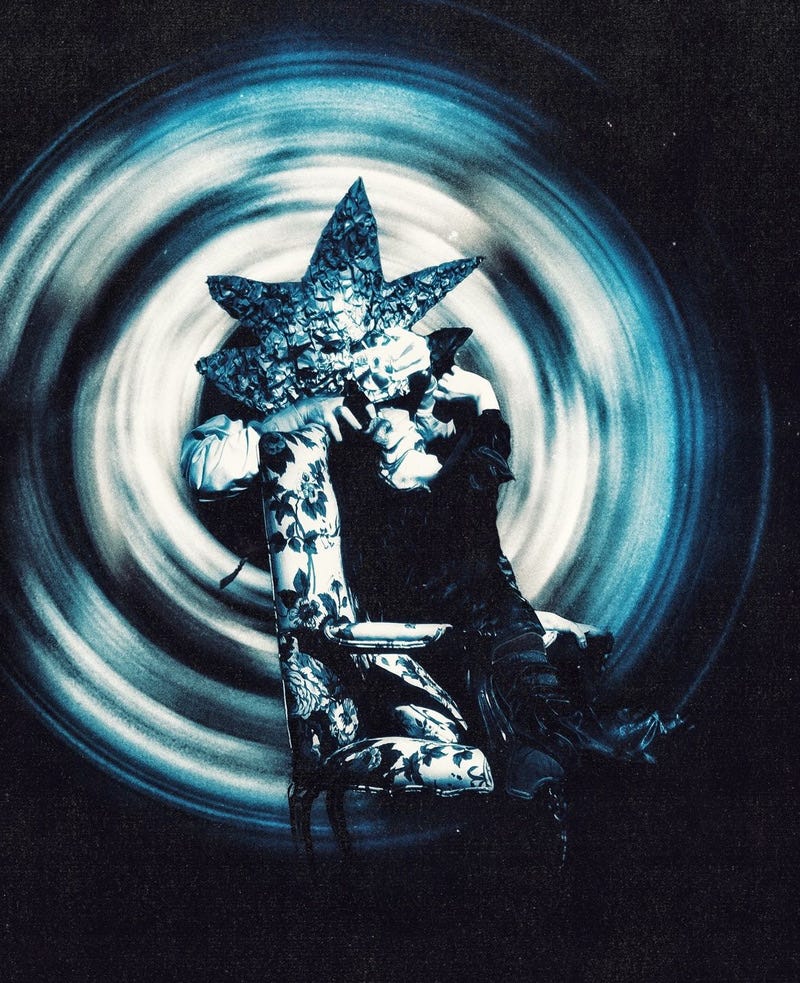

On the concert stage, Matt and Mica of Magdalena Bay act out a wordless skit, manifesting characters from the music video for their song “Image” for the live audience’s viewing pleasure. Mica, in her blue alien suit, struggles and screams without sound on a living room chair after too much watching TV. Matt, face obscured by a giant, gaudy mask (like a red starfish, with crude holes in the center for eyes), holds a disk aloft for all to see, and brings it down slowly towards her forehead. She is powerless to stop it. The disk slides in, and she stops thrashing, goes limp. From where I was in the audience, I could see behind the proscenium magic trick, Matt sliding the disk along the left side of Mica’s face, then hiding it swiftly out of view. This is real life.

We numb ourselves with the things we love. We remind ourselves that we, too, could be vital. Art can change everything as easily as it could keep everything the same. Peter Brook coined the concept of the Deadly Theatre1. It’s the kind of theatre that is soulless and cash-grabbing. It’s the kind I’ve made a living selling tickets to go see. It’s not what I got into this industry to do, but it’s where I’ve been shelved for the time being. Is it killing me? Or am I killing the theatre?

RIP, Peter Brook. You would’ve loved Magdalena Bay.

They performed their new album, Imaginal Disk, front to back, with only a handful of extraneous songs added to the setlist. The stage was replete with DIY-grade props. The centerpiece was a screen like a magic mirror, like the gored-out center of a simplified biblical angel, white wings spread out on the sides. There was a living room chair, floral and grandmotherly, and a white picket fence downstage of a ruby red backdrop. There was a hood of sunflower petals, a mask like a demon bug, the aforementioned starfish mask. Mica wore three outfits, each of which had been lifted straight the duo’s recent music videos. The cape she wore was identical to the ones my classmates and I used as wings to play birds when we studied theatre in Germany. The concert had a straightforward artistic vision in a decidedly camp vein. It was narrative-based in the same way that opera and ballet are. It was uncanny and associative, like something I’d seen before in someone else’s dream. It was theatre.

On my first listen to the record, I surrendered the urge to identify what any of it meant. The lyrics are cryptic, the art direction is high-concept, and it is clear that a story is at play, even if the nuances of it are not so easy to parse. I had no interest in scouring interviews or poring through Genius annotations to compile an official analysis. I didn’t need to know what mundane inner workings of their real lives produced these songs, this performance, the concept itself. When I saw Gustav Klimt’s The Kiss in Vienna, I didn’t bother reading the placard. I looked at it, and I felt.

I Saw the TV Glow is, canonically, a trans allegory. I do not identify as trans; yet, I identify with being an outsider. I am familiar with the hazy sense that something isn’t right in this place, and, if only I could get out of here, then life could really begin. I am well-versed in the experience of a false home: biding time, training myself to ignore the pressure, coddling myself with the few things that bring me comfort. In this practice, I know, I can lose myself.

I am largely uninterested in allegory as the chief means by which to interpret a piece of art, especially one as expansive and immersive as I Saw the TV Glow or Imaginal Disk. I’ve found that allegorical analysis goes like so: A = B, C = D, and there is nothing else it could be. Why discuss whether A = X, when we’ve already proven that A = B?

But art is not math. There is not one right answer, categorically proven. There is, of course, the original artist’s intent. There are, of course, interpretations that we can strike from the list because they don’t make any kind of logical sense or engender emotional resonance.

Understanding art is a gut thing. I don’t say this to excuse the twisting of interpretations to fit spiteful agendas; I say it to encourage identification, analysis, love of art. Images are inconclusive, expansive, endlessly associative. The way you feel about them — if you are really feeling them, true and honest — is the only interpretation you ultimately need to worry about. Forget Pitchfork, forget The Hollywood Reporter. Remember that you, and everybody else, consist of a brain stuck behind a stubborn set of eyeballs, with no way of knowing for certain if you see the same shade of red as the person who walks beside you.

I Saw the TV Glow is a sophomore feature film, and Imaginal Disk is a sophomore studio album. Maybe, once you do something all the way once, you unlock a dimension of creative permission that lets you create a brand new image. Scripts and lyrics aside, the cores of these pieces lie in their images. The disk in Mica’s forehead. Owen’s head through the TV set. These works that deal so integrally with identity, perception, and the nature of reality are transcendent where they are wordless. I don’t want to articulate. I want to watch. I want to listen. I want to complete the cycle so I can repeat the cycle someday.

Back in May, on that rainy, backwards day in the Midnight Realm, I began to come to my senses around the time that the clouds began to part. Somewhere between storm and sunshine, I stopped crying and I reached a point of understanding. I’ll never be happy until I become an artist. I batted away well-meaning voices that told me I already was one. I knew that there was more I needed to do. I needed to be a real Artist, a life-changing one. Not a player for the Deadly Theatre.

I went to the bathroom, I stared at the grout between the shower tiles, and I found rainbows moving around them. The way they shifted reminded me of cars down residential streets, and I watched like a bird on a power line. I wondered how I was supposed to go back to real life and pretend I didn’t know there were colors in between the cracks.

Of course, I couldn’t.

Brook, Peter. The Empty Space. New York: Atheneum, 1968.